FastAPI

FastAPI is a modern, fast (high-performance), web framework for building APIs with Python 3.7+ based on standard Python type hints.

Features:

- Fast

- Fast to Code

- Fewer bugs

- Intuitive

- Easy

- Short

- Robust

- Standard-based

- OpenAPI

- JSON Schema

Requirements

- Python 3.7 +

- Starlette

- Pydantic

Installation

pip3 install -U pip "fastapi[all]" ujson email-validator orjson "uvicorn[standard]"

❯ pip freeze

anyio==3.6.2

click==8.1.3

fastapi==0.88.0

h11==0.14.0

httptools==0.5.0

idna==3.4

pydantic==1.10.2

python-dotenv==0.21.0

PyYAML==6.0

sniffio==1.3.0

starlette==0.22.0

typing_extensions==4.4.0

uvicorn==0.20.0

uvloop==0.17.0

watchfiles==0.18.1

websockets==10.4

Example

Create it

from typing import Union

from fastapi import FastAPI

app = FastAPI()

@app.get("/")

def read_root_sync():

return {"Hello": "World"}

@app.get("/items/{item_id}")

def read_item_sync(item_id: int, q: Union[str, None] = None):

"""

Read a single item synchronously

:param item_id: int

:param q: an optional string query parameter

:return:

"""

return {"item_id": item_id, "q": q}

Example Upgrade

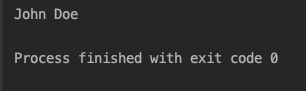

3. Python Types

def get_full_name(first_name: str, last_name: str) -> str:

full_name = first_name.title() + ' ' + last_name.title()

return full_name

print(get_full_name("john", "doe"))

We are using colons (:), not equals (=).

Simple Types

You can use, for example:

intfloatboolbytes

def get_items(item_a: str, item_b: int, item_c: float, item_d: bool, item_e: bytes):

return item_a, item_b, item_c, item_d, item_d, item_e

List

def process_items(items: list[str]):

for item in items:

print(item)

Those internal types in the square brackets are called “type parameters”.

In this case,

stris the type parameter passed tolist

Tuple and Set

def process_items(items_t: tuple[int, int, str], items_s: set[bytes]):

return items_t, items_s

This means:

- The variable

items_tis atuplewith 3 items, anint, anotherint, and astr. - The variable

items_sis aset, and each of its items is of typebytes.

Dict

To define a dict, you pass 2 type parameters, separated by commas.

The first type parameter is for the keys of the dict.

The second type parameter is for the values of the dict:

def process_items(prices: dict[str, float]):

for item_name, item_price in prices.items():

print(item_name)

print(item_price)

Union

You can declare that a variable can be any of several types, for example, an int or a str.

In Python 3.10 there’s also an alternative syntax where you can put the possible types separated by a vertical bar (|).

def process_item(item: int | str):

print(item)

Possibly None

You can declare that a value could have a type, like str, but that it could also be None.

def say_hi(name: str | None = None):

if name is not None:

print(f"Hey {name}!")

else:

print("Hello World")

Generic Types

These types that take type parameters in square brackets are called Generic types or Generics, for example:

You can use the same builtin types as generics (with square brackets and types inside):

listtuplesetdict

you can use the vertical bar (|) to declare unions of types.

Classes as Types

You can also declare a class as the type of a variable.

class Person:

def __init__(self, name: str):

self.name = name

def get_person_name(one_person: Person) -> str:

return one_person.name

p1 = Person(name="Trump")

print(get_person_name(p1))

Pydantic Models

Pydantic is a Python library to perform data validation.

You declare the “shape” of the data as classes with attributes.

And each attribute has a type.

from datetime import datetime

from pydantic import BaseModel

class User(BaseModel):

id: int

name = "John Smith"

signup_ts: datetime | None = None

friends: list[int] = []

external_data = {

"id": "123",

"signup_ts": "2017-06-01 12:22",

"friends": [1, "2", b"3"],

}

user = User(**external_data)

print(user)

print(user.id)

First Steps

When building APIs, you normally use these specific HTTP methods to perform a specific action.

Normally you use:

POST: to create data.GET: to read data.PUT: to update data.DELETE: to delete data.

So, in OpenAPI, each of the HTTP methods is called an “operation”.

We are going to call them “operations” too.

Path parameters

Order matters

Like /users/me, let’s say that it’s to get data about the current user.

And then you can also have a path /users/{user_id} to get data about a specific user by some user ID.

Because path operations are evaluated in order, you need to make sure that the path for /users/me is declared before the one for /users/{user_id}:

Predefined values

class ModelName(str, Enum):

alexnet = "alexnet"

resnet = 'resnet'

lenet = 'lenet'

@app.get("/models/{model_name}")

async def read_model(model_name: ModelName):

if model_name is ModelName.alexnet:

return {"model_name": model_name, "message": "Deep Learning FTW"}

elif model_name.value == 'lenet':

return {"model_name": model_name, "message": "LeCNN all the images"}

return {"model_name": model_name, "message": "Have some residuals"}

Query Parameters

When you declare other function parameters that are not part of the path parameters, they are automatically interpreted as “query” parameters.

fake_items_db = [{"item_name": "Foo"}, {"item_name": "Bar"}, {"item_name": "Baz"}]

@app.get("/items/")

async def read_items_query(skip: int = 0, limit: int = 10):

return fake_items_db[skip:skip + limit]

The query is the set of key-value pairs that go after the ? in a URL, separated by & characters.

For example, in the URL:

http://127.0.0.1:8000/items/?skip=0&limit=10

Defaults of query parameters

As query parameters are not a fixed part of a path, they can be optional and can have default values.

The same way, you can declare optional query parameters, by setting their default to None:

fake_items_db = [{"item_name": "Foo"}, {"item_name": "Bar"}, {"item_name": "Baz"}]

@app.get("/items/")

async def read_items_query(skip: int = 0, limit: int = 10):

return fake_items_db[skip:skip + limit]

@app.get("/items_query/{item_id}")

async def read_item_query(item_id: int, q: str | None = None):

if q:

return {"item_id": item_id, "q": q}

return {"item_id": item_id}

Multiple path and query parameters

You can declare multiple path parameters and query parameters at the same time, FastAPI knows which is which.

And you don’t have to declare them in any specific order.

@app.get("/users/{user_id}/items/{item_id}")

async def read_user_item(user_id: int, item_id: int, q: str | None = None, short: bool = False):

item = {"item_id": item_id, "owner_id": user_id}

if q:

item.update({"q": q})

if not short:

item.update(

{"description": "This is an amazing item that has a long description"}

)

return item

Required query parameters

But when you want to make a query parameter required, you can just not declare any default value:

Request Body

When you need to send data from a client (let’s say, a browser) to your API, you send it as a request body.

A request body is data sent by the client to your API. A response body is the data your API sends to the client.

Your API almost always has to send a response body. But clients don’t necessarily need to send request bodies all the time.

class Item2(BaseModel):

name: str

price: float

description: str | None = None

tax: float | None = None

@app.post("/items2/")

async def create_item(item: Item2):

return item

when a model attribute has a default value, it is not required. Otherwise, it is required. Use

Noneto make it just optional.

{

"name": "Foo",

"description": "An optional description",

"price": 45.2,

"tax": 3.5

}

@app.post("/items2/")

async def create_item(item: Item2):

item_dict = item.dict()

if item.tax:

price_with_tax = item.price + item.tax

item_dict.update({"price_with_tax": price_with_tax})

return item_dict

Request body + path parameters

@app.put("items2/{item_id}")

async def create_item2(item_id: int, item: Item2):

return {"item_id": item_id, **item.dict()}

Request body + path + query parameters

@app.put("/items22/{item_id}")

async def update_item2(item_id: int, item: Item2, q: str | None = None):

result = {"item_id": item_id, **item.dict()}

if q:

result.update({"q": q})

return result

- If the parameter is also declared in the path, it will be used as a path parameter.

- If the parameter is of a singular type (like

int,float,str,bool, etc) it will be interpreted as a query parameter. - If the parameter is declared to be of the type of a Pydantic model, it will be interpreted as a request body.

Query Parameters and String Validators

FastAPI allows you to declare additional information and validation for your parameters.

Optional

@app.get("/items-optional/")

async def read_items_optional(q: str | None = None):

results = {"items": [{"item_id": "Foo"}, {"item_id": "Bar"}]}

if q:

results.update({"q": q})

return results

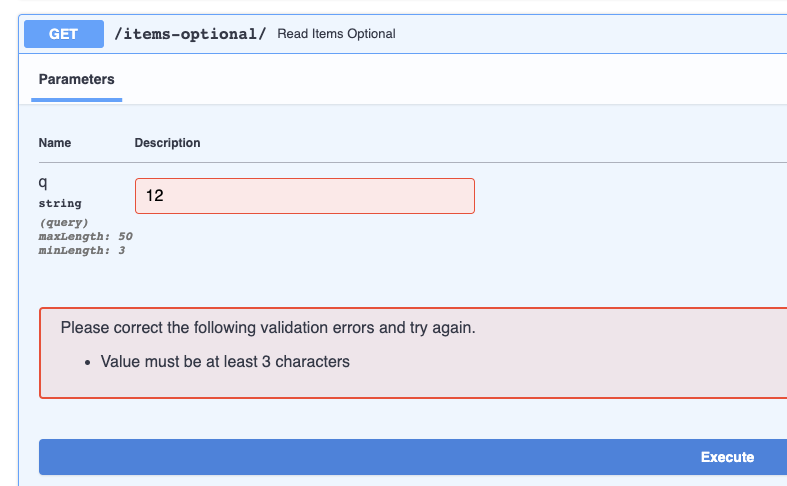

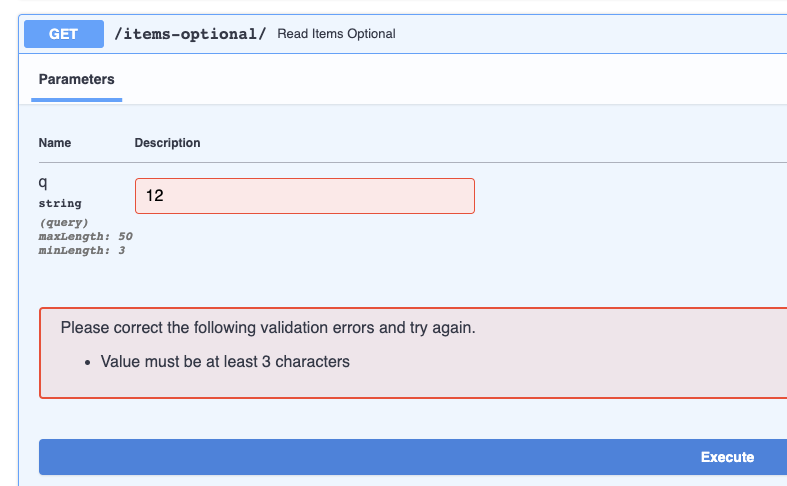

Additional Validation

We are going to enforce that even though q is optional, whenever it is provided, its length doesn’t exceed 50 characters.

@app.get("/items-optional/")

async def read_items_optional(q: str | None = Query(default=None, max_length=50)):

results = {"items": [{"item_id": "Foo"}, {"item_id": "Bar"}]}

if q:

results.update({"q": q})

return results

Add more validations

You can also add a parameter min_length:

@app.get("/items-optional/")

async def read_items_optional(q: str | None = Query(default=None, min_length=3, max_length=50)):

results = {"items": [{"item_id": "Foo"}, {"item_id": "Bar"}]}

if q:

results.update({"q": q})

return results

Add regular expressions

@app.get("/items-optional/")

async def read_items_optional(q: str | None = Query(default=None, min_length=3, max_length=50, regex="^fixedquery$")):

results = {"items": [{"item_id": "Foo"}, {"item_id": "Bar"}]}

if q:

results.update({"q": q})

return results

Required

@app.get("/items-required/")

async def read_items_optional(q: str = Query(min_length=3, max_length=50, regex="^fixedquery$")):

results = {"items": [{"item_id": "Foo"}, {"item_id": "Bar"}]}

if q:

results.update({"q": q})

return results

Required with Ellipsis (…)

@app.get("/items-required-ellipsis/")

async def read_items_optional(q: str = Query(default=..., max_length=5)):

results = {"items": [{"item_id": "Foo"}, {"item_id": "Bar"}]}

if q:

results.update({"q": q})

return results

...: it is a special single value, it is part of Python and is called “Ellipsis”.It is used by Pydantic and FastAPI to explicitly declare that a value is required.

Required with None

You can declare that a parameter can accept None, but that it’s still required. This would force clients to send a value, even if the value is None.

To do that, you can declare that None is a valid type but still use default=...:

@app.get("/items/")

async def read_items(q: str | None = Query(default=..., min_length=3)):

results = {"items": [{"item_id": "Foo"}, {"item_id": "Bar"}]}

if q:

results.update({"q": q})

return results

Pydantic Required, instead of Ellipsis(…)

from pydantic import Required

@app.get("/items/")

async def read_items(q: str = Query(default=Required, min_length=3)):

results = {"items": [{"item_id": "Foo"}, {"item_id": "Bar"}]}

if q:

results.update({"q": q})

return results

Query parameter list / multiple value

@app.get("/items-query-list")

async def read_items_query_list(q: list[str] | None = Query(default=None)):

query_items = {"q": q}

return query_items

To declare a query parameter with a type of

list, like in the example above, you need to explicitly useQuery, otherwise it would be interpreted as a request body.

Query parameter list / multiple values with defaults

@app.get("/items/")

async def read_items(q: list[str] = Query(default=["foo", "bar"])):

query_items = {"q": q}

return query_items

using list

@app.get("/items/")

async def read_items(q: list = Query(default=[])):

query_items = {"q": q}

return query_items

Declare more metadata

@app.get("/items-query-metadata")

async def read_items_query_metadata(

q: str | None = Query(

default=None,

title="Query String Title",

description="Query String Description",

min_length=3, )

):

results = {"items": [{"item_id": "foo"}, {"item_id": "bar"}]}

if q:

results.update({"q": q})

return results

Alias parameters

Imagine that you want the parameter to be item-query.

Like in:

http://127.0.0.1:8000/items/?item-query=foobaritems

But item-query is not a valid Python variable name.

@app.get("/items-query-alias")

async def read_items_query_alias(q: str | None = Query(default=None, alias="item-query")):

results = {"items": [{"item_id": "foo"}, {"item_id": "bar"}]}

if q:

results.update({"q": q})

return results

Deprecating parameters

@app.get("/items/")

async def read_items(

q: str

| None = Query(

default=None,

alias="item-query",

title="Query string",

description="Query string for the items to search in the database that have a good match",

min_length=3,

max_length=50,

regex="^fixedquery$",

deprecated=True,

)

):

results = {"items": [{"item_id": "Foo"}, {"item_id": "Bar"}]}

if q:

results.update({"q": q})

return results

Exclude from OpenAPI and automcatic document system

from fastapi import FastAPI, Query

app = FastAPI()

@app.get("/items/")

async def read_items(

hidden_query: str | None = Query(default=None, include_in_schema=False)

):

if hidden_query:

return {"hidden_query": hidden_query}

else:

return {"hidden_query": "Not found"}

Path Parameters and numeric validators

@app.get("/items-path-parameters/{item_id}")

async def read_items_path_parameters(

item_id: int = Path(title="the ID of the item to get"),

q: str | None = Query(default=None, alias="item-query")):

results = {"item_id": item_id}

if q:

results.update({"q": q})

return results

Order the parameters as you need, tricks

If you want to declare the q query parameter without a Query nor any default value, and the path parameter item_id using Path, and have them in a different order, Python has a little special syntax for that.

Pass *, as the first parameter of the function.

Python won’t do anything with that *, but it will know that all the following parameters should be called as keyword arguments (key-value pairs), also known as kwargs. Even if they don’t have a default value.

@app.get("/items/{item_id}")

async def read_items(*, item_id: int = Path(title="The ID of the item to get"), q: str):

results = {"item_id": item_id}

if q:

results.update({"q": q})

return results

Number validations

greater than or equal

@app.get("/items/{item_id}")

async def read_items(

*, item_id: int = Path(title="The ID of the item to get", ge=1), q: str

):

results = {"item_id": item_id}

if q:

results.update({"q": q})

return results

greater than and less than or equal

from fastapi import FastAPI, Path

app = FastAPI()

@app.get("/items/{item_id}")

async def read_items(

*,

item_id: int = Path(title="The ID of the item to get", gt=0, le=1000),

q: str,

):

results = {"item_id": item_id}

if q:

results.update({"q": q})

return results

floats, greater than and less than

@app.get("/items/{item_id}")

async def read_items(

*,

item_id: int = Path(title="The ID of the item to get", ge=0, le=1000),

q: str,

size: float = Query(gt=0, lt=10.5)

):

results = {"item_id": item_id}

if q:

results.update({"q": q})

return results

Body - Multiple Parameters

Mix Path, Query and body parameters

you can also declare body parameters as optional, by setting the default to None:

class Item3(BaseModel):

name: str

description: str | None = None

price: float

tax: float | None = None

@app.put("/items-body/{item_id}")

async def update_item3(

*, # count the parameters as key word parameters

item_id: int = Path(title="the ID of the item to update", ge=0, le=1000),

q: str | None = None,

item: Item3 | None = None,

):

results = {"item_id": item_id}

if q:

results.update({"q": q})

if item:

results.update({"item": item})

return results

Multiple body parameters

class User3(BaseModel):

username: str

full_name: str | None = None

@app.put("/items-body2/{item_id}")

async def update_item3(

*, # count the parameters as key word parameters

item_id: int = Path(title="the ID of the item to update", ge=0, le=1000),

q: str | None = None,

item: Item3,

user: User3,

):

results = {"item_id": item_id}

if q:

results.update({"q": q})

if item:

results.update({"item": item})

return results

Singular values in body

@app.put("/items-importance/{item_id}")

async def update_item(item_id: int, item: Item3, user: User3, importance: int = Body()):

results = {"item_id": item_id, "item": item, "user": user, "importance": importance}

return results

Multiple body params and query

@app.put("/items/{item_id}")

async def update_item(

*,

item_id: int,

item: Item,

user: User,

importance: int = Body(gt=0),

q: str | None = None

):

results = {"item_id": item_id, "item": item, "user": user, "importance": importance}

if q:

results.update({"q": q})

return results

Embed a single body parameter

Let’s say you only have a single item body parameter from a Pydantic model Item.

{

"name": "Foo",

"description": "The pretender",

"price": 42.0,

"tax": 3.2

}

But if you want it to expect a JSON with a key item and inside of it the model contents, as it does when you declare extra body parameters, you can use the special Body parameter embed:

@app.put("/items/{item_id}")

async def update_item(item_id: int, item: Item = Body(embed=True)):

results = {"item_id": item_id, "item": item}

return results

In this case FastAPI will expect a body like:

{

"item": {

"name": "Foo",

"description": "The pretender",

"price": 42.0,

"tax": 3.2

}

}

Body Fields

you can declare validation and metadata inside of Pydantic models using Pydantic’s Field.

class Item4(BaseModel):

name: str

description: str | None = Field(

default=None,

title="The description of the item",

max_length=300

)

price: float

tax: float | None = None

Declare model attributes

You can then use Field with model attributes:

class Item4(BaseModel):

name: str

description: str | None = Field(

default=None,

title="The description of the item",

max_length=300

)

price: float = Field(gt=0, description="The price must be greater than 0")

tax: float | None = None

@app.put("/items4/{item_id}")

async def update_item4(item_id: int, item: Item4 = Body(embed=True)):

results = {"item_id": item_id, "item": item}

return results

Body - Nested Models

With FastAPI, you can define, validate, document, and use arbitrarily deeply nested models (thanks to Pydantic).

List Fields

You can define an attribute to be a subtype. For example, a Python list:

class Item5(BaseModel):

name: str

description: str | None = None

price: float

tax: float | None = None

tags: list = []

@app.put("/items5/{item_id}")

async def update_item(item_id: int, item: Item5):

results = {"item_id": item_id, "item": item}

return results

Declare a list with a type parameter

class Item(BaseModel):

name: str

description: str | None = None

price: float

tax: float | None = None

tags: list[str] = []

Set types

But then we think about it, and realize that tags shouldn’t repeat, they would probably be unique strings.

And Python has a special data type for sets of unique items, the set.

class Item(BaseModel):

name: str

description: str | None = None

price: float

tax: float | None = None

tags: set[str] = set()

// request body

{

"name": "string",

"description": "string",

"price": 0,

"tax": 0,

"tags": [1,2,3,1]

}

// response body

{

"item_id": 5,

"item": {

"name": "string",

"description": "string",

"price": 0,

"tax": 0,

"tags": [

"2",

"1",

"3"

]

}

}

Nested Models

Each attribute of a Pydantic model has a type.

But that type can itself be another Pydantic model.

So, you can declare deeply nested JSON “objects” with specific attribute names, types and validations.

All that, arbitrarily nested.

class Image(BaseModel):

url: str

name: str

class Item6(BaseModel):

name: str

description: str | None = None

price: float

tax: float | None = None

tags: set[str] = set()

image: Image | None = None

Special types and validation

For example, as in the Image model we have a url field, we can declare it to be instead of a str, a Pydantic’s HttpUrl:

from pydantic import BaseModel, HttpUrl

class Image(BaseModel):

url: HttpUrl

name: str

{

"name": "string",

"description": "string",

"price": 0,

"tax": 0,

"tags": [],

"image": {

"url": "https",

"name": "string"

}

}

{

"detail": [

{

"loc": [

"body",

"image",

"url"

],

"msg": "invalid or missing URL scheme",

"type": "value_error.url.scheme"

}

]

}

Attributes with lists of submodels

You can also use Pydantic models as subtypes of list, set, etc:

class Item7(BaseModel):

name: str

description: str | None = None

price: float

tax: float | None = None

tags: set[str] = set()

images: list[Image] | None = None

Deeply nested models

class Offer(BaseModel):

name: str

description: str | None = None

price: float

items: list[Item]

Item nested images, and Offer nested Item

Bodies of pure lists

If the top level value of the JSON body you expect is a JSON array (a Python list), you can declare the type in the parameter of the function, the same as in Pydantic models:

@app.post("/images/multiple/")

async def create_multiple_images(images: list[Image]):

return images

Bodies of arbitrary dicts

You can also declare a body as a dict with keys of some type and values of other type.

Without having to know beforehand what are the valid field/attribute names (as would be the case with Pydantic models).

This would be useful if you want to receive keys that you don’t already know.

Other useful case is when you want to have keys of other type, e.g. int.

That’s what we are going to see here.

In this case, you would accept any dict as long as it has int keys with float values:

@app.post("/index-weights/")

async def create_index_weights(weights: dict[int, float]):

return weights

{ "1" : 3.44 }

curl -X 'POST' \

'http://127.0.0.1:8000/index-weights/' \

-H 'accept: application/json' \

-H 'Content-Type: application/json' \

-d '{

"1": 3.14,

}'

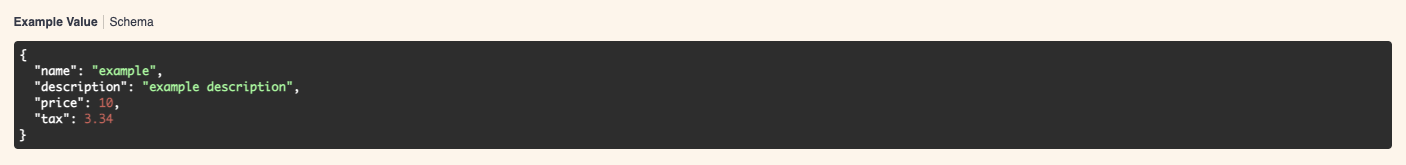

Declare Request Example Data

You can declare examples of the data your app can receive.

Pydantic schema_extra

class Item8(BaseModel):

name: str

description: str | None = None

price: float

tax: float | None = None

class Config:

schema_extra = {

"example": {

"name": "example",

"description": "example description",

"price": 10.0,

"tax": 3.34

}

}

@app.put("/items8/{item_id}")

async def update_item8(item_id: int, item: Item8):

results = {"item_id": item_id, "item": item}

return results

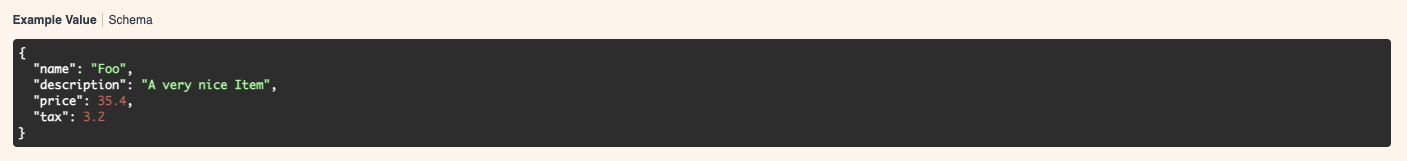

Field additional arguments

When using Field() with Pydantic models, you can also declare extra info for the JSON Schema by passing any other arbitrary arguments to the function.

You can use this to add example for each field:

from pydantic import BaseModel, Field

class Item9(BaseModel):

name: str = Field(example="Foo")

description: str | None = Field(default=None, example="A very nice Item")

price: float = Field(example=35.4)

tax: float | None = Field(default=None, example=3.2)

example and examples in OpenAPI¶

When using any of:

Path()Query()Header()Cookie()Body()Form()File()

you can also declare a data example or a group of examples with additional information that will be added to OpenAPI.

Body with example

@app.put("/items/{item_id}")

async def update_item(

item_id: int,

item: Item = Body(

example={

"name": "Foo",

"description": "A very nice Item",

"price": 35.4,

"tax": 3.2,

},

),

):

results = {"item_id": item_id, "item": item}

return results

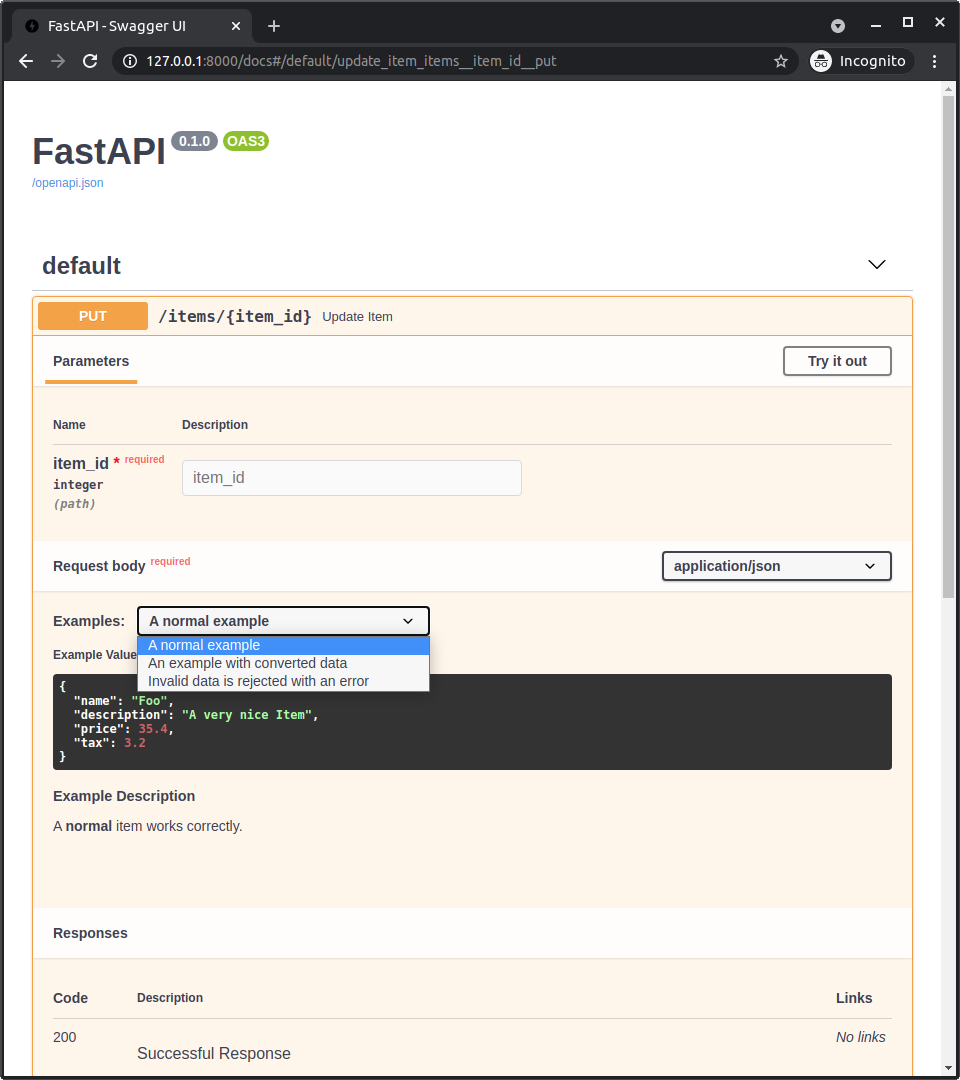

Body with multiple examples

Alternatively to the single example, you can pass examples using a dict with multiple examples, each with extra information that will be added to OpenAPI too.

@app.put("/items/{item_id}")

async def update_item(

*,

item_id: int,

item: Item = Body(

examples={

"normal": {

"summary": "A normal example",

"description": "A **normal** item works correctly.",

"value": {

"name": "Foo",

"description": "A very nice Item",

"price": 35.4,

"tax": 3.2,

},

},

"converted": {

"summary": "An example with converted data",

"description": "FastAPI can convert price `strings` to actual `numbers` automatically",

"value": {

"name": "Bar",

"price": "35.4",

},

},

"invalid": {

"summary": "Invalid data is rejected with an error",

"value": {

"name": "Baz",

"price": "thirty five point four",

},

},

},

),

):

results = {"item_id": item_id, "item": item}

return results

Extra Data Types

common data types, like:

intfloatstrbool

Other data types

Here are some of the additional data types you can use:

-

UUID:

- A standard “Universally Unique Identifier”, common as an ID in many databases and systems.

- In requests and responses will be represented as a

str.

-

datetime.datetime:

- A Python

datetime.datetime. - In requests and responses will be represented as a

strin ISO 8601 format, like:2008-09-15T15:53:00+05:00.

- A Python

-

datetime.date:

- Python

datetime.date. - In requests and responses will be represented as a

strin ISO 8601 format, like:2008-09-15.

- Python

-

datetime.time:

- A Python

datetime.time. - In requests and responses will be represented as a

strin ISO 8601 format, like:14:23:55.003.

- A Python

-

datetime.timedelta:

- A Python

datetime.timedelta. - In requests and responses will be represented as a

floatof total seconds. - Pydantic also allows representing it as a “ISO 8601 time diff encoding”, see the docs for more info.

- A Python

-

frozenset:

-

In requests and responses, treated the same as a

set:

- In requests, a list will be read, eliminating duplicates and converting it to a

set. - In responses, the

setwill be converted to alist. - The generated schema will specify that the

setvalues are unique (using JSON Schema’suniqueItems).

- In requests, a list will be read, eliminating duplicates and converting it to a

-

-

bytes:

- Standard Python

bytes. - In requests and responses will be treated as

str. - The generated schema will specify that it’s a

strwithbinary“format”.

- Standard Python

-

Decimal:

- Standard Python

Decimal. - In requests and responses, handled the same as a

float.

- Standard Python

- You can check all the valid pydantic data types here: Pydantic data types.

@app.put("/items10/{item_id}")

async def read_items(

item_id: UUID,

start_datetime: datetime | None = Body(default=None),

end_datetime: datetime | None = Body(default=None),

repeat_at: time | None = Body(default=None),

process_after: timedelta | None = Body(default=None),

):

start_process = start_datetime + process_after

duration = end_datetime - start_process

return {

"item_id": item_id,

"start_datetime": start_datetime,

"end_datetime": end_datetime,

"repeat_at": repeat_at,

"process_after": process_after,

"start_process": start_process,

"duration": duration,

}

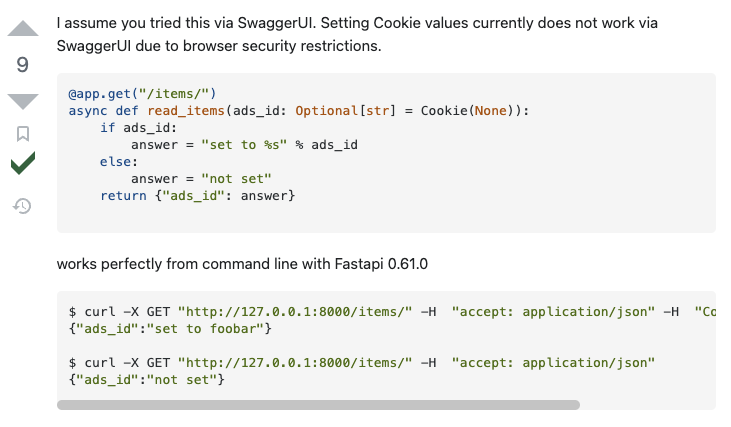

Cookie Parameters

You can define Cookie parameters the same way you define Query and Path parameters.

@app.get("/items11/")

async def read_items11(ads_id: str | None = Cookie(default=None)):

print(ads_id)

return {"ads_id": ads_id}

Header Parameters

You can define Header parameters the same way you define Query, Path and Cookie parameters.

@app.get("/header/")

async def read_header(user_agent: str | None = Header(default=None)):

return {"User-Agent": user_agent}

{

"User-Agent": "Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh; Intel Mac OS X 10_15_7) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/108.0.0.0 Safari/537.36"

}

Header has a little extra functionality on top of what Path, Query and Cookie provide.

Most of the standard headers are separated by a “hyphen” character, also known as the “minus symbol” (-).

But a variable like user-agent is invalid in Python.

So, by default, Header will convert the parameter names characters from underscore (_) to hyphen (-) to extract and document the headers.

Also, HTTP headers are case-insensitive, so, you can declare them with standard Python style (also known as “snake_case”).

So, you can use user_agent as you normally would in Python code, instead of needing to capitalize the first letters as User_Agent or something similar.

It is possible to receive duplicate headers. That means, the same header with multiple values.

You can define those cases using a list in the type declaration.

You will receive all the values from the duplicate header as a Python list.

@app.get("/header/")

async def read_header(user_agent: str | None = Header(default=None), x_token: str | None = Header(default=None)):

return {"User-Agent": user_agent, "X-Token Values": x_token}

Response Model

You can declare the model used for the response with the parameter response_model in any of the path operations:

@app.get()@app.post()@app.put()@app.delete()

Notice that

response_modelis a parameter of the “decorator” method (get,post, etc). Not of your path operation function, like all the parameters and body.

@app.get("/response_body/", response_model=Item8)

async def read_response_body():

return {"item_id": 1, "name": "Foo", "description": "A very nice Item", "price": 10.0, "tax": 3.34}

class UserIn(BaseModel):

username: str

email: EmailStr

password: SecretStr

full_name: str | None = None

class UserOut(BaseModel):

username: str

email: EmailStr

full_name: str | None = None

@app.post("/users/", response_model=UserOut)

async def create_user(user: UserIn):

return user

class Item(BaseModel):

name: str

description: str | None = None

price: float

tax: float = 10.5

items = {

"foo": {"name": "Foo", "price": 50.2},

"bar": {"name": "Bar", "description": "The Bar fighters", "price": 62, "tax": 20.2},

"baz": {

"name": "Baz",

"description": "There goes my baz",

"price": 50.2,

"tax": 10.5,

},

}

@app.get(

"/items/{item_id}/name",

response_model=Item,

response_model_include={"name", "description"},

)

async def read_item_name(item_id: str):

return items[item_id]

@app.get("/items/{item_id}/public", response_model=Item, response_model_exclude={"tax"})

async def read_item_public_data(item_id: str):

return items[item_id]

@app.get("/items/{item_id}", response_model=Item, response_model_exclude_unset=True)

async def read_item(item_id: str):

return items[item_id]

You can also use:

response_model_exclude_defaults=Trueresponse_model_exclude_none=Trueas described in the Pydantic docs for

exclude_defaultsandexclude_none.

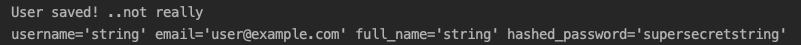

Extra Models

Continuing with the previous example, it will be common to have more than one related model.

This is especially the case for user models, because:

- The input model needs to be able to have a password.

- The output model should not have a password.

- The database model would probably need to have a hashed password.

class UserBase(BaseModel):

username: str

email: EmailStr

full_name: str | None = None

class UserIn(UserBase):

password: str

class UserOut(UserBase):

pass

class UserInDB(UserBase):

hashed_password: str

def fake_password_hasher(raw_password: str):

return "supersecret" + raw_password

def fake_save_user(user_in: UserIn):

hashed_password = fake_password_hasher(user_in.password)

user_in_db = UserInDB(**user_in.dict(), hashed_password=hashed_password)

print("User saved! ..not really")

return user_in_db

@app.post("/users-extra/", response_model=UserOut)

async def create_user(user_in: UserIn):

user_saved = fake_save_user(user_in)

print(user_saved)

return user_saved

curl -X 'POST' \

'http://127.0.0.1:8000/users-extra/' \

-H 'accept: application/json' \

-H 'Content-Type: application/json' \

-d '{

"username": "string",

"email": "[email protected]",

"full_name": "string",

"password": "string"

}'

response

{

"username": "string",

"email": "[email protected]",

"full_name": "string"

}

Union or anyOf

You can declare a response to be the Union of two types, that means, that the response would be any of the two.

It will be defined in OpenAPI with anyOf.

class BaseItem(BaseModel):

description: str

type: str

class CarItem(BaseItem):

type = "car"

class PlaneItem(BaseItem):

type = "plane"

size: int

items = {

"item1": {"description": "All my friends drive a low rider", "type": "car"},

"item2": {

"description": "Music is my aeroplane, it's my aeroplane",

"type": "plane",

"size": 5,

},

}

@app.get("/items/{item_id}", response_model=Union[PlaneItem, CarItem])

async def read_item(item_id: str):

return items[item_id]

List of models

@app.get("/items/", response_model=list[Item])

async def read_items():

return items

Response with arbitrary dict

@app.get("/keyword-weights/", response_model=dict[str, float])

async def read_keyword_weights():

return {"foo": 2.3, "bar": 3.4}

Response Status Code

@app.post("/items/", status_code=201)

async def create_item(name: str):

return {"name": name}

In short:

-

100and above are for “Information”. You rarely use them directly. Responses with these status codes cannot have a body. -

200and above are for “Successful” responses. These are the ones you would use the most.

200is the default status code, which means everything was “OK”.- Another example would be

201, “Created”. It is commonly used after creating a new record in the database. - A special case is

204, “No Content”. This response is used when there is no content to return to the client, and so the response must not have a body.

-

300and above are for “Redirection”. Responses with these status codes may or may not have a body, except for304, “Not Modified”, which must not have one. -

400and above are for “Client error” responses. These are the second type you would probably use the most.

- An example is

404, for a “Not Found” response. - For generic errors from the client, you can just use

400.

- An example is

-

500and above are for server errors. You almost never use them directly. When something goes wrong at some part in your application code, or server, it will automatically return one of these status codes.

Form Data

When you need to receive form fields instead of JSON, you can use Form.

To use forms, first install python-multipart.

E.g. pip install python-multipart.

For example, in one of the ways the OAuth2 specification can be used (called “password flow”) it is required to send a username and password as form fields.

The spec requires the fields to be exactly named username and password, and to be sent as form fields, not JSON.

Data from forms is normally encoded using the “media type”

application/x-www-form-urlencoded.But when the form includes files, it is encoded as

multipart/form-data. You’ll read about handling files in the next chapter.

@app.post("/login/")

async def login(username: str = Form(), password: str = Form()):

return {"username": username}

Request Files

pip install python-multipart

@app.post("/files/")

async def create_file(file: bytes = File()):

# whole content will be saved in the memory as bytes

print(file)

return {"file_size": len(file)}

@app.post("/uploadfile/")

async def create_upload_file(file: UploadFile):

contents = await file.read()

print(contents)

return {"filename": file.filename, "content_type": file.content_type, "file": file}

{

"filename": "CleanShot 2022-12-05 at 10.32.57.png",

"content_type": "image/png",

"file": {

"filename": "CleanShot 2022-12-05 at 10.32.57.png",

"content_type": "image/png",

"file": {},

"headers": {

"content-disposition": "form-data; name=\"file\"; filename=\"CleanShot 2022-12-05 at 10.32.57.png\"",

"content-type": "image/png"

}

}

}

UploadFile¶ UploadFile has the following attributes:

filename: A str with the original file name that was uploaded (e.g. myimage.jpg).

content_type: A str with the content type (MIME type / media type) (e.g. image/jpeg).

file: A SpooledTemporaryFile (a file-like object). This is the actual Python file that you can pass directly to other functions or libraries that expect a “file-like” object.

UploadFile has the following async methods. They all call the corresponding file methods underneath (using the internal SpooledTemporaryFile).

write(data): Writes data (str or bytes) to the file.

read(size): Reads size (int) bytes/characters of the file.

seek(offset): Goes to the byte position offset (int) in the file.

E.g., await myfile.seek(0) would go to the start of the file.

This is especially useful if you run await myfile.read() once and then need to read the contents again.

close(): Closes the file.

As all these methods are async methods, you need to “await” them.

For example, inside of an async path operation function you can get the contents with:

contents = await myfile.read()

If you are inside of a normal def path operation function, you can access the UploadFile.file directly, for example:

contents = myfile.file.read()

Optional File Upload

@app.post("/files/")

async def create_file(file: bytes | None = File(default=None, description="A file read as bytes")):

# whole content will be saved in the memory as bytes

if not file:

return {"message": "No file sent"}

else:

return {"file_size": len(file)}

@app.post("/uploadfile/")

async def create_upload_file(file: UploadFile | None = File(default=None, description="A file read as UploadFile")):

if not file:

return {"message": "No upload file sent"}

else:

contents = await file.read()

print(contents)

return {"filename": file.filename, "content_type": file.content_type, "file": file}

Multiple File Uploads

@app.post("/multi-files/")

async def create_multi_files(files: list[bytes] = File(description="Multiple files as bytes")):

return {"file_sizes": [len(file) for file in files]}

@app.post("/upload-multiple-files/")

async def create_upload_files2(files: list[UploadFile] = File(description="Multiple upload files as UploadFile")):

return {"filenames": [file.filename for file in files]}

Request Forms and Files

@app.post("/token-files/")

async def create_file(

file: bytes = File(), fileb: UploadFile = File(), token: str = Form()

):

return {

"file_size": len(file),

"token": token,

"fileb_content_type": fileb.content_type,

}

curl -X 'POST' \

'http://127.0.0.1:8000/token-files/' \

-H 'accept: application/json' \

-H 'Content-Type: multipart/form-data' \

-F 'file=@CleanShot 2022-12-05 at 10.32.57.png;type=image/png' \

-F 'fileb=@CleanShot 2022-12-05 at 10.32.57.png;type=image/png' \

-F 'token=1111'

{

"file_size": 19851,

"token": "1111",

"fileb_content_type": "image/png"

}

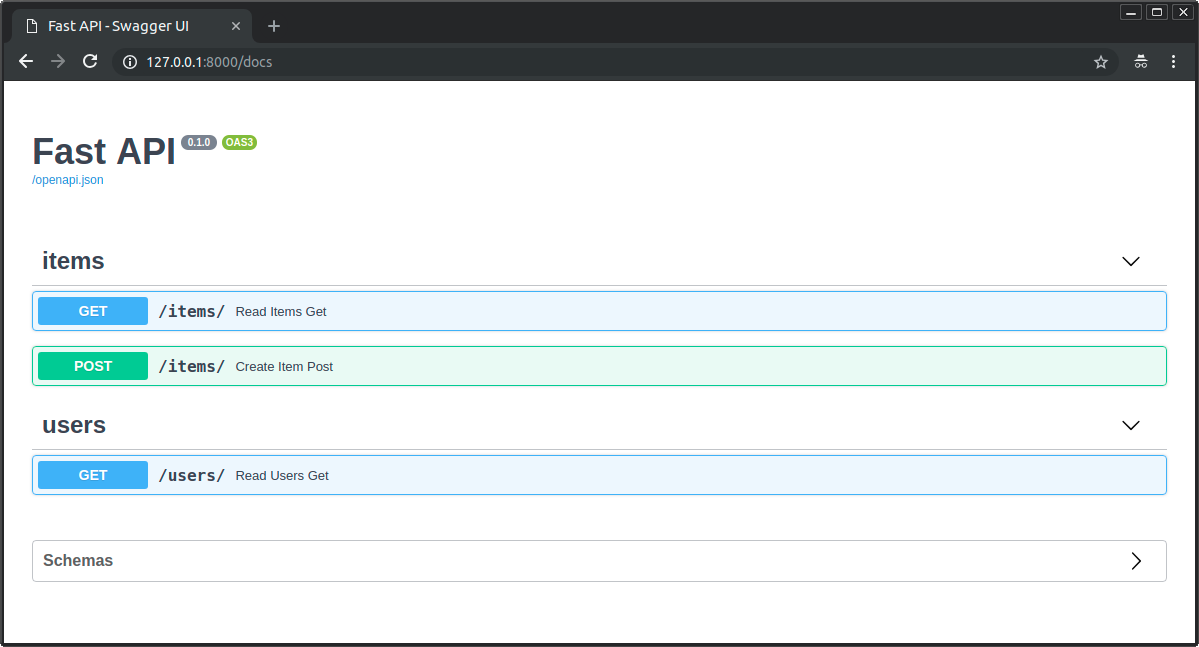

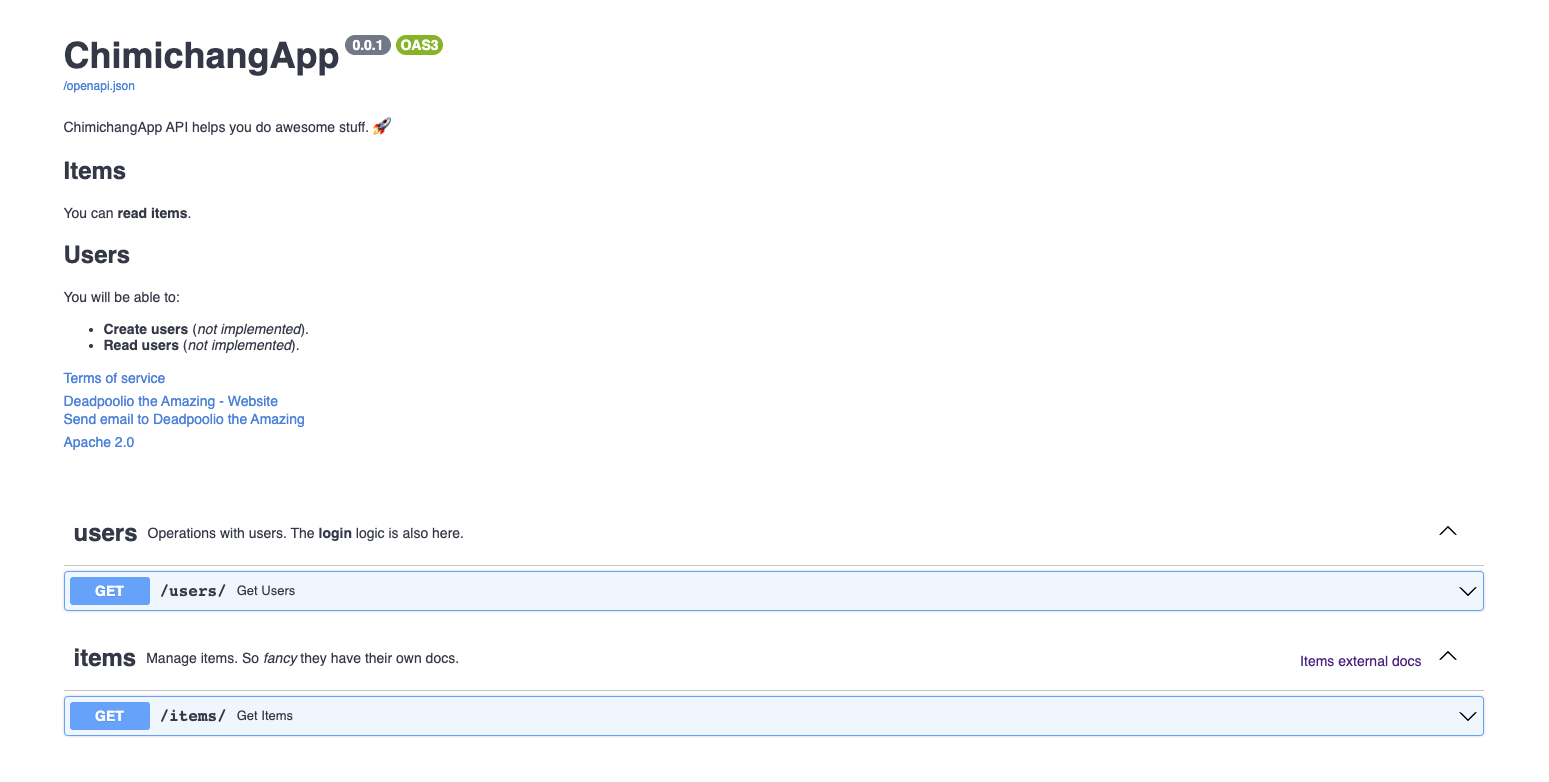

Path Operation Configuration

Tags

@app.post("/items/", response_model=Item, tags=["items"])

async def create_item(item: Item):

return item

@app.get("/items/", tags=["items"])

async def read_items():

return [{"name": "Foo", "price": 42}]

@app.get("/users/", tags=["users"])

async def read_users():

return [{"username": "johndoe"}]

Tags with Enums

class Tags(Enum):

items = "items"

users = "users"

@app.get("/items/", tags=[Tags.items])

async def get_items():

return ["Portal gun", "Plumbus"]

@app.get("/users/", tags=[Tags.users])

async def read_users():

return ["Rick", "Morty"]

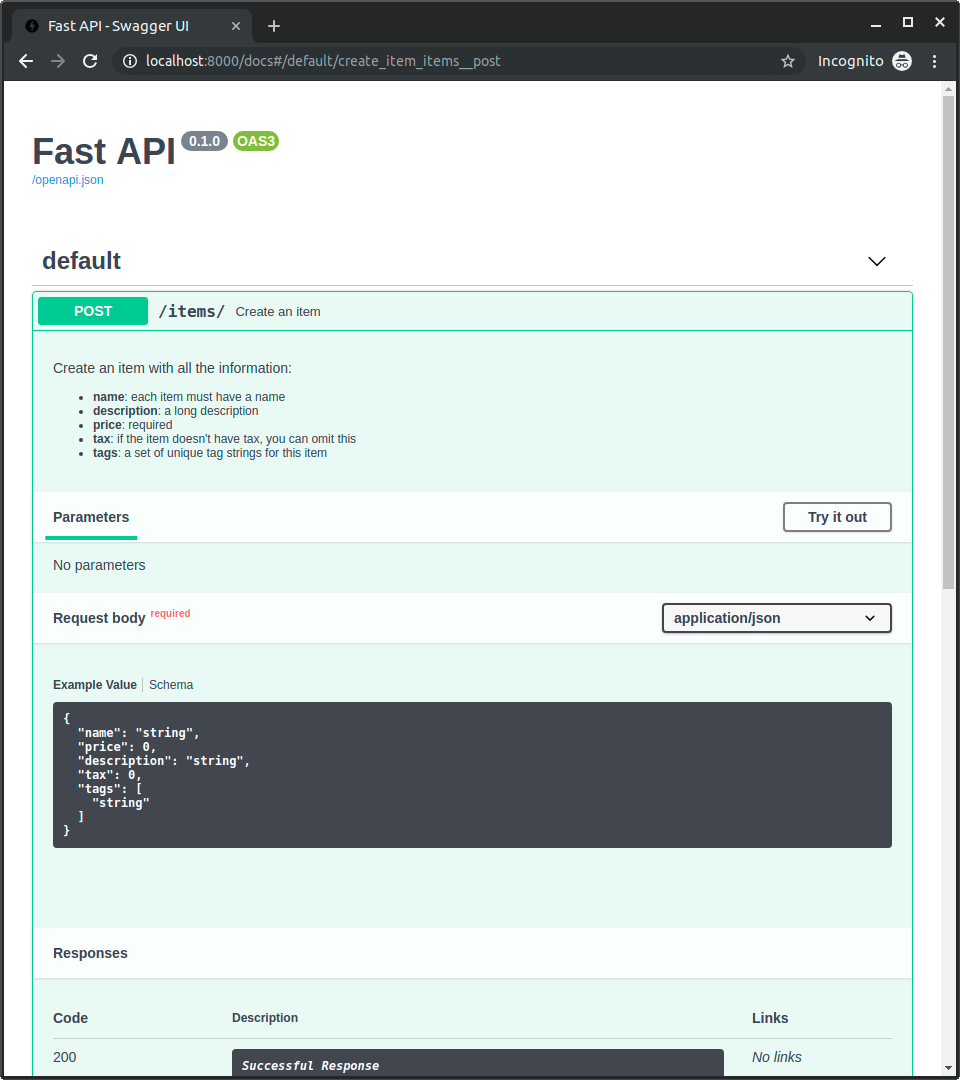

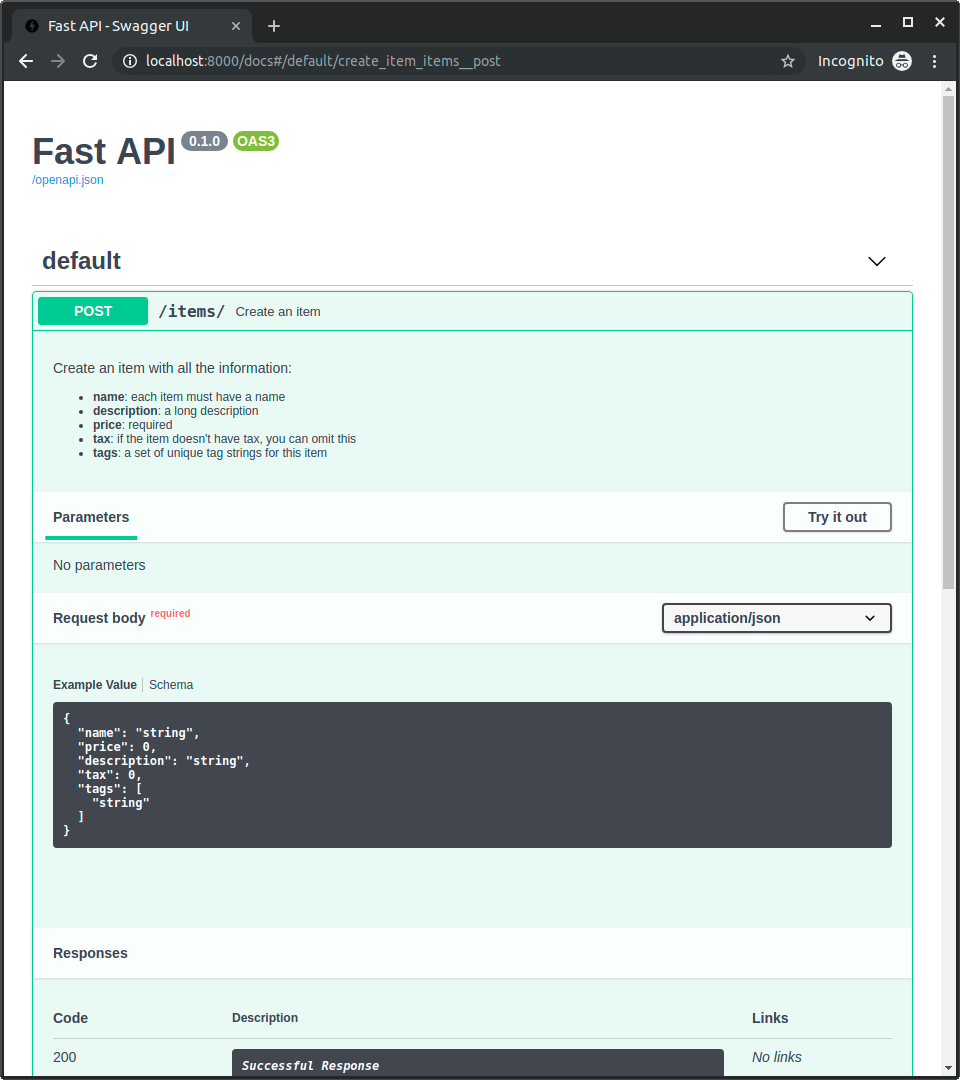

Description from docstring

@app.post("/items/", response_model=Item, summary="Create an item")

async def create_item(item: Item):

"""

Create an item with all the information:

- **name**: each item must have a name

- **description**: a long description

- **price**: required

- **tax**: if the item doesn't have tax, you can omit this

- **tags**: a set of unique tag strings for this item

"""

return item

Deprecated

@app.get("/elements/", tags=["items"], deprecated=True)

async def read_elements():

return [{"item_id": "Foo"}]

JSON Compatible Encoder

There are some cases where you might need to convert a data type (like a Pydantic model) to something compatible with JSON (like a dict, list, etc).

For example, if you need to store it in a database.

Let’s imagine that you have a database fake_db that only receives JSON compatible data.

For example, it doesn’t receive datetime objects, as those are not compatible with JSON.

from fastapi.encoders import jsonable_encoder

@app.put("/items/{id}")

def update_item(id: str, item: Item):

json_compatible_item_data = jsonable_encoder(item)

fake_db[id] = json_compatible_item_data

Body Updates (PUT or PATCH)

class Item(BaseModel):

name: str | None = None

description: str | None = None

price: float | None = None

tax: float = 10.5

tags: list[str] = []

items = {

"foo": {"name": "Foo", "price": 50.2},

"bar": {"name": "Bar", "description": "The bartenders", "price": 62, "tax": 20.2},

"baz": {"name": "Baz", "description": None, "price": 50.2, "tax": 10.5, "tags": []},

}

@app.get("/items/{item_id}", response_model=Item)

async def read_item(item_id: str):

return items[item_id]

@app.patch("/items/{item_id}", response_model=Item)

async def update_item(item_id: str, item: Item):

stored_item_data = items[item_id]

stored_item_model = Item(**stored_item_data)

update_data = item.dict(exclude_unset=True)

updated_item = stored_item_model.copy(update=update_data)

items[item_id] = jsonable_encoder(updated_item)

return updated_item

Dependencies

FastAPI has a very powerful but intuitive Dependency Injection system.

“Dependency Injection” means, in programming, that there is a way for your code (in this case, your path operation functions) to declare things that it requires to work and use: “dependencies”.

And then, that system (in this case FastAPI) will take care of doing whatever is needed to provide your code with those needed dependencies (“inject” the dependencies).

This is very useful when you need to:

- Have shared logic (the same code logic again and again).

- Share database connections.

- Enforce security, authentication, role requirements, etc.

- And many other things…

All these, while minimizing code repetition.

async def common_parameters(q: str | None = None, skip: int = 0, limit: int = 100):

return {"q": q, "skip": skip, "limit": limit}

@app.get("/items-depends/")

async def read_items(commons: dict = Depends(common_parameters)):

return commons

@app.get("/users-depends/")

async def read_users(commons: dict = Depends(common_parameters)):

return commons

- Calling your dependency (“dependable”) function with the correct parameters.

- Get the result from your function.

- Assign that result to the parameter in your path operation function.

With the Dependency Injection system, you can also tell FastAPI that your path operation function also “depends” on something else that should be executed before your path operation function, and FastAPI will take care of executing it and “injecting” the results.

Other common terms for this same idea of “dependency injection” are:

- resources

- providers

- services

- injectables

- components

For example, let’s say you have 4 API endpoints (path operations):

/items/public//items/private//users/{user_id}/activate/items/pro/

then you could add different permission requirements for each of them just with dependencies and sub-dependencies:

Classes as Dependencies

The key factor is that a dependency should be a “callable”.

A “callable” in Python is anything that Python can “call” like a function.

class CommonQueryParams:

def __init__(self, q: str | None = None, skip: int = 0, limit: int = 100):

self.q = q

self.skip = skip

self.limit = limit

@app.get("/items-common-depends/")

async def read_items(commons: CommonQueryParams = Depends()):

response = {}

if commons.q:

response.update({"q": commons.q})

items = fake_items_db[commons.skip: commons.skip + commons.limit]

response.update({"items": items})

return response

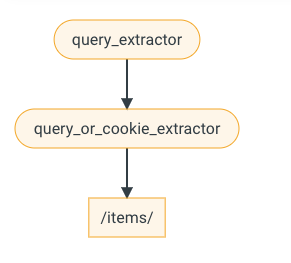

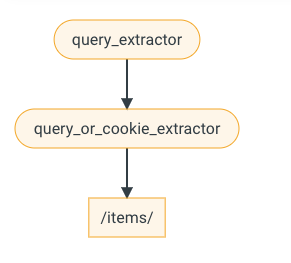

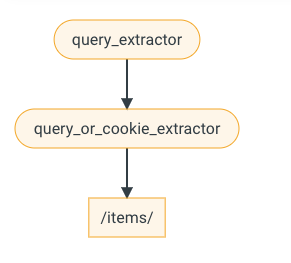

Sub-dependencies

You can create dependencies that have sub-dependencies.

def query_extractor(q: str | None = None):

return q

def query_or_cookie_extractor(

q: str = Depends(query_extractor), last_query: str | None = Cookie(default=None)

):

# If the user didn't provide any query q, we use the last query used, which we saved to a cookie before.

if not q:

return last_query

return q

@app.get("/items12/")

async def read_query(query_or_default: str = Depends(query_or_cookie_extractor)):

return {"q_or_cookie": query_or_default}

Dependencies in path operation decorators

In some cases you don’t really need the return value of a dependency inside your path operation function.

Or the dependency doesn’t return a value.

But you still need it to be executed/solved.

For those cases, instead of declaring a path operation function parameter with Depends, you can add a list of dependencies to the path operation decorator.

async def verify_token(x_token: str = Header()):

if x_token != "fake-super-secret-token":

raise HTTPException(status_code=400, detail="X-Token header invalid")

async def verify_key(x_key: str = Header()):

if x_key != "fake-super-secret-key":

raise HTTPException(status_code=400, detail="X-Key header invalid")

return x_key

@app.get("/items12/", dependencies=[Depends(verify_token), Depends(verify_key)])

async def read_items():

return [{"item": "Foo"}, {"item": "Bar"}]

Global Dependency

app = FastAPI(dependencies=[Depends(verify_token), Depends(verify_key)])

Dependency with Yield

FastAPI supports dependencies that do some extra steps after finishing.

To do this, use yield instead of return, and write the extra steps after.

Any function that is valid to use with:

would be valid to use as a FastAPI dependency.

In fact, FastAPI uses those two decorators internally.

If you use a try block in a dependency with yield, you’ll receive any exception that was thrown when using the dependency.

async def get_db():

db = DBSession()

try:

yield db

finally:

db.close()

Sub Dependency with Yield

FastAPI will make sure that the “exit code” in each dependency with yield is run in the correct order.

For example, dependency_c can have a dependency on dependency_b, and dependency_b on dependency_a:

async def dependency_a():

dep_a = generate_dep_a()

try:

yield dep_a

finally:

dep_a.close()

async def dependency_b(dep_a=Depends(dependency_a)):

dep_b = generate_dep_b()

try:

yield dep_b

finally:

dep_b.close(dep_a)

async def dependency_c(dep_b=Depends(dependency_b)):

dep_c = generate_dep_c()

try:

yield dep_c

finally:

dep_c.close(dep_b)

sequenceDiagram

participant client as Client

participant handler as Exception handler

participant dep as Dep with yield

participant operation as Path Operation

participant tasks as Background tasks

Note over client,tasks: Can raise exception for dependency, handled after response is sent

Note over client,operation: Can raise HTTPException and can change the response

client ->> dep: Start request

Note over dep: Run code up to yield

opt raise

dep -->> handler: Raise HTTPException

handler -->> client: HTTP error response

dep -->> dep: Raise other exception

end

dep ->> operation: Run dependency, e.g. DB session

opt raise

operation -->> dep: Raise HTTPException

dep -->> handler: Auto forward exception

handler -->> client: HTTP error response

operation -->> dep: Raise other exception

dep -->> handler: Auto forward exception

end

operation ->> client: Return response to client

Note over client,operation: Response is already sent, can't change it anymore

opt Tasks

operation -->> tasks: Send background tasks

end

opt Raise other exception

tasks -->> dep: Raise other exception

end

Note over dep: After yield

opt Handle other exception

dep -->> dep: Handle exception, can't change response. E.g. close DB session.

end

Context Managers

“Context Managers” are any of those Python objects that you can use in a with statement.

For example, you can use with to read a file:

with open("./somefile.txt") as f:

contents = f.read()

print(contents)

Underneath, the open("./somefile.txt") creates an object that is a called a “Context Manager”.

When the with block finishes, it makes sure to close the file, even if there were exceptions.

In Python, you can create Context Managers by creating a class with two methods: __enter__() and __exit__().

class MySuperContextManager:

def __init__(self):

self.db = DBSession()

def __enter__(self):

return self.db

def __exit__(self, exc_type, exc_value, traceback):

self.db.close()

async def get_db():

with MySuperContextManager() as db:

yield db

Security

There are many ways to handle security, authentication and authorization.

To put it simply, authentication is about who you are, while authorization is about what you are allowed to do.

OAuth2¶

OAuth2 is a specification that defines several ways to handle authentication and authorization.

It is quite an extensive specification and covers several complex use cases.

It includes ways to authenticate using a “third party”.

That’s what all the systems with “login with Facebook, Google, Twitter, GitHub” use underneath.

OpenID Connect is another specification, based on OAuth2.

It just extends OAuth2 specifying some things that are relatively ambiguous in OAuth2, to try to make it more interoperable.

OpenAPI (previously known as Swagger) is the open specification for building APIs (now part of the Linux Foundation).

FastAPI is based on OpenAPI.

OpenAPI defines the following security schemes:

apiKey: an application specific key that can come from:- A query parameter.

- A header.

- A cookie.

http: standard HTTP authentication systems, including:bearer: a headerAuthorizationwith a value ofBearerplus a token. This is inherited from OAuth2.- HTTP Basic authentication.

- HTTP Digest, etc.

oauth2: all the OAuth2 ways to handle security (called “flows”).- Several of these flows are appropriate for building an OAuth 2.0 authentication provider (like Google, Facebook, Twitter, GitHub, etc):

implicitclientCredentialsauthorizationCode

- But there is one specific “flow” that can be perfectly used for handling authentication in the same application directly:

password: some next chapters will cover examples of this.

- Several of these flows are appropriate for building an OAuth 2.0 authentication provider (like Google, Facebook, Twitter, GitHub, etc):

openIdConnect: has a way to define how to discover OAuth2 authentication data automatically.- This automatic discovery is what is defined in the OpenID Connect specification.

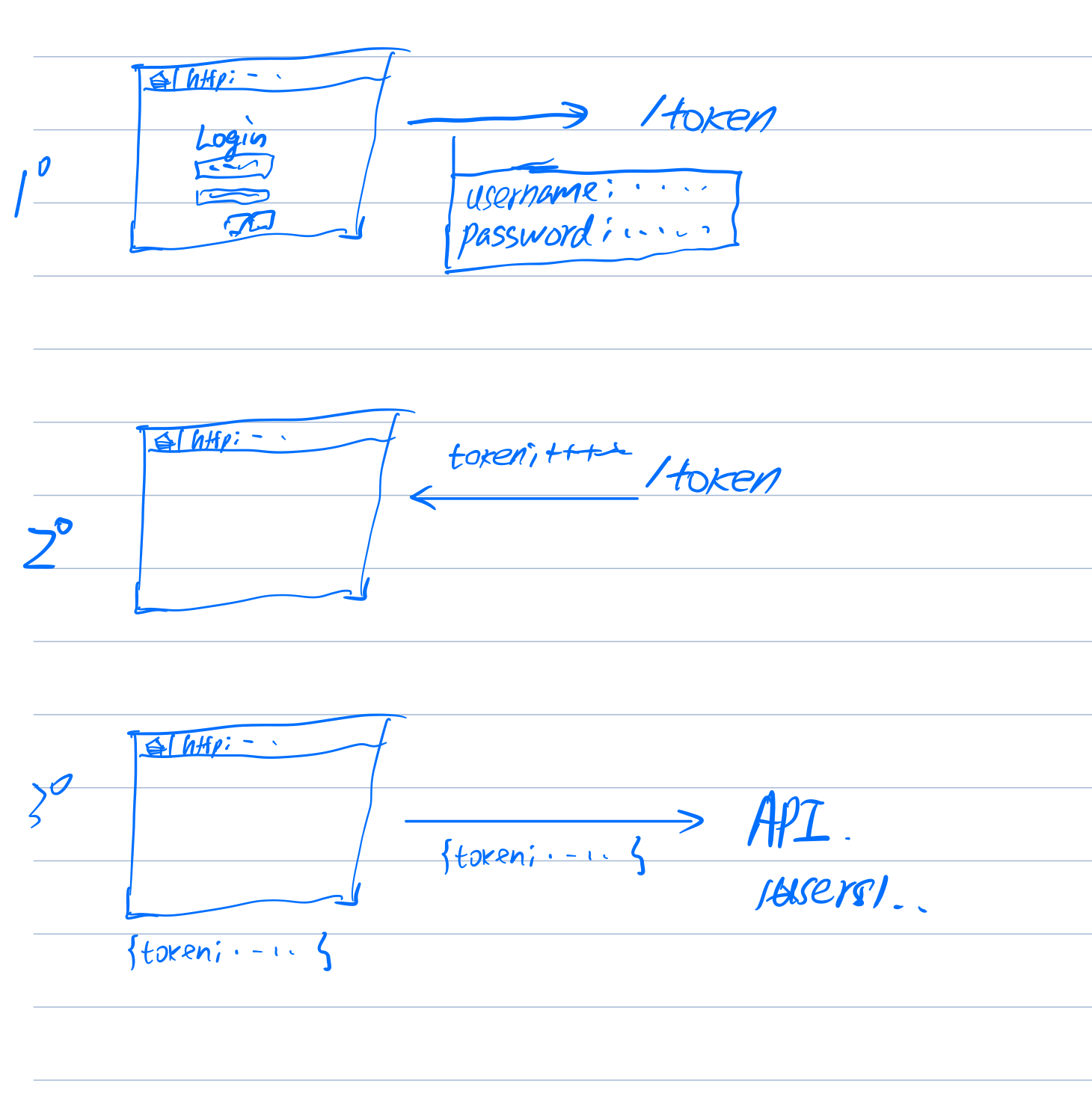

username and password

oauth2_scheme = OAuth2PasswordBearer(tokenUrl="token")

@app.get("/items13/")

async def read_items(token: str = Depends(oauth2_scheme)):

return {"token": token}

OAuth2 was designed so that the backend or API could be independent of the server that authenticates the user.

But in this case, the same FastAPI application will handle the API and the authentication.

-

A “token” is just a string with some content that we can use later to verify this user.

-

Normally, a token is set to expire after some time.

- So, the user will have to log in again at some point later.

- And if the token is stolen, the risk is less. It is not like a permanent key that will work forever (in most of the cases).

When we create an instance of the OAuth2PasswordBearer class we pass in the tokenUrl parameter. This parameter contains the URL that the client (the frontend running in the user’s browser) will use to send the username and password in order to get a token.

oauth2_scheme = OAuth2PasswordBearer(tokenUrl="token")

# tokenUrl="token" refers to a relative URL token, it's equivalent to ./token

@app.get("/items13/")

async def read_items(token: str = Depends(oauth2_scheme)):

# This dependency will provide a str that is assigned to the parameter token of the path operation function.

return {"token": token}

Get current user

class User4(BaseModel):

username: str

email: str | None = None

full_name: str | None = None

disabled: bool | None = None

def fake_decode_token(token):

user = User4(

username=token + "fake_decoded",

email="[email protected]",

full_name="John Doe",

disabled=False

)

print(user)

return user

async def get_current_user(token: str = Depends(oauth2_scheme)):

print(token)

user = fake_decode_token(token)

print(user)

return user

@app.get("/users-token/me")

async def read_users_me(current_user: User4 = Depends(get_current_user)):

return current_user

Simple OAuth2 with Password and Bearer

OAuth2 specifies that when using the “password flow” (that we are using) the client/user must send a username and password fields as form data.

scope¶

The spec also says that the client can send another form field “scope”.

The spec also says that the client can send another form field “scope”.

The form field name is scope (in singular), but it is actually a long string with “scopes” separated by spaces.

Each “scope” is just a string (without spaces).

They are normally used to declare specific security permissions, for example:

users:readorusers:writeare common examples.instagram_basicis used by Facebook / Instagram.https://www.googleapis.com/auth/driveis used by Google.

In OAuth2 a “scope” is just a string that declares a specific permission required.

fake_users_db = {

"johndoe": {

"username": "johndoe",

"full_name": "John Doe",

"email": "[email protected]",

"hashed_password": "fakehashedsecret",

"disabled": False,

},

"alice": {

"username": "alice",

"full_name": "Alice Wonderson",

"email": "[email protected]",

"hashed_password": "fakehashedsecret2",

"disabled": True,

},

}

def fake_hash_password(password: str) -> str:

return "fakehashed" + password

class UserInDB(User4):

hashed_password: str

def get_user(db, username: str):

if username in db:

user_dict = db[username]

return UserInDB(**user_dict)

def fake_decode_token4(token):

# This doesn't provide any security at all

# Check the next version

user = get_user(fake_users_db, token)

return user

async def get_current_user(token: str = Depends(oauth2_scheme)):

user = fake_decode_token(token)

if not user:

raise HTTPException(

status_code=status.HTTP_401_UNAUTHORIZED,

detail="Invalid authentication credentials",

headers={"WWW-Authenticate": "Bearer"},

)

return user

async def get_current_active_user(current_user: User4 = Depends(get_current_user)):

if current_user.disabled:

raise HTTPException(status_code=400, detail="Inactive user")

return current_user

@app.post("/token")

async def login(form_data: OAuth2PasswordRequestForm = Depends()):

print(form_data.username)

print(form_data.password)

user_dict = fake_users_db.get(form_data.username)

if not user_dict:

raise HTTPException(status_code=400, detail="Incorrect username or password")

user = UserInDB(**user_dict)

hashed_password = fake_hash_password(form_data.password)

if not hashed_password == user.hashed_password:

raise HTTPException(status_code=400, detail="Incorrect username or password")

return {"access_token": user.username, "token_type": "bearer"}

@app.get("/users-secure/me")

async def read_users_me(current_user: User4 = Depends(get_current_active_user)):

return current_user

“Hashing” means: converting some content (a password in this case) into a sequence of bytes (just a string) that looks like gibberish.

Whenever you pass exactly the same content (exactly the same password) you get exactly the same gibberish.

But you cannot convert from the gibberish back to the password.

UserInDB(**user_dict) means:

Pass the keys and values of the user_dict directly as key-value arguments, equivalent to:

UserInDB(

username = user_dict["username"],

email = user_dict["email"],

full_name = user_dict["full_name"],

disabled = user_dict["disabled"],

hashed_password = user_dict["hashed_password"],

)

OAuth2 with Password (and hashing), Bearer with JWT tokens

Let’s make the application actually secure, using JWT tokens and secure password hashing.

JWT means “JSON Web Tokens”.

It’s a standard to codify a JSON object in a long dense string without spaces. It looks like this:

eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJzdWIiOiIxMjM0NTY3ODkwIiwibmFtZSI6IkpvaG4gRG9lIiwiaWF0IjoxNTE2MjM5MDIyfQ.SflKxwRJSMeKKF2QT4fwpMeJf36POk6yJV_adQssw5c

It is not encrypted, so, anyone could recover the information from the contents.

But it’s signed. So, when you receive a token that you emitted, you can verify that you actually emitted it.

# Hashing tokens

from passlib.context import CryptContext

from jose import JWTError, jwt

# to get a string like this run:

# openssl rand -hex 32

SECRET_KEY = "09d25e094faa6ca2556c818166b7a9563b93f7099f6f0f4caa6cf63b88e8d3e7"

ALGORITHM = "HS256"

ACCESS_TOKEN_EXPIRE_MINUTES = 30

fake_users_db2 = {

"johndoe": {

"username": "johndoe",

"full_name": "John Doe",

"email": "[email protected]",

"hashed_password": "$2b$12$EixZaYVK1fsbw1ZfbX3OXePaWxn96p36WQoeG6Lruj3vjPGga31lW",

"disabled": False,

}

}

class Token(BaseModel):

access_token: str

token_type: str

class TokenData(BaseModel):

username: str | None = None

class User5(BaseModel):

username: str

email: str | None = None

full_name: str | None = None

disabled: bool | None = None

class UserInDB5(User5):

hashed_password: str

pwd_context = CryptContext(schemes=["bcrypt"], deprecated="auto")

def verify_password(plain_password, hashed_password):

return pwd_context.verify(plain_password, hashed_password)

def get_password_hash(password):

return pwd_context.hash(password)

def get_user5(db, username: str):

if username in db:

user_dict = db[username]

return UserInDB(**user_dict)

def authenticate_user(fake_db5, username: str, password: str):

user = get_user(fake_db5, username)

if not user:

return False

if not verify_password(password, user.hashed_password):

return False

return user

def create_access_token(data: dict, expires_delta: timedelta | None = None):

to_encode = data.copy()

if expires_delta:

expire = datetime.utcnow() + expires_delta

else:

expire = datetime.utcnow() + timedelta(minutes=15)

to_encode.update({"exp": expire})

encoded_jwt = jwt.encode(to_encode, SECRET_KEY, algorithm=ALGORITHM)

return encoded_jwt

async def get_current_user5(token: str = Depends(oauth2_scheme)):

credentials_exception = HTTPException(

status_code=status.HTTP_401_UNAUTHORIZED,

detail="Could not validate credentials",

headers={"WWW-Authenticate": "Bearer"},

)

try:

payload = jwt.decode(token, SECRET_KEY, algorithms=[ALGORITHM])

username: str = payload.get("sub")

if username is None:

raise credentials_exception

token_data = TokenData(username=username)

except JWTError:

raise credentials_exception

user = get_user(fake_users_db2, username=token_data.username)

if user is None:

raise credentials_exception

return user

async def get_current_active_user(current_user: User5 = Depends(get_current_user5)):

if current_user.disabled:

raise HTTPException(status_code=400, detail="Inactive user")

return current_user

@app.post("/token", response_model=Token)

async def login_for_access_token(form_data: OAuth2PasswordRequestForm = Depends()):

user = authenticate_user(fake_users_db2, form_data.username, form_data.password)

if not user:

raise HTTPException(

status_code=status.HTTP_401_UNAUTHORIZED,

detail="Incorrect username or password",

headers={"WWW-Authenticate": "Bearer"},

)

access_token_expires = timedelta(minutes=ACCESS_TOKEN_EXPIRE_MINUTES)

access_token = create_access_token(

data={"sub": user.username}, expires_delta=access_token_expires

)

return {"access_token": access_token, "token_type": "bearer"}

@app.get("/users-jwt/me/", response_model=User5)

async def read_users_me(current_user: User5 = Depends(get_current_active_user)):

return current_user

@app.get("/users/me/items/")

async def read_own_items(current_user: User5 = Depends(get_current_active_user)):

return [{"item_id": "Foo", "owner": current_user.username}]

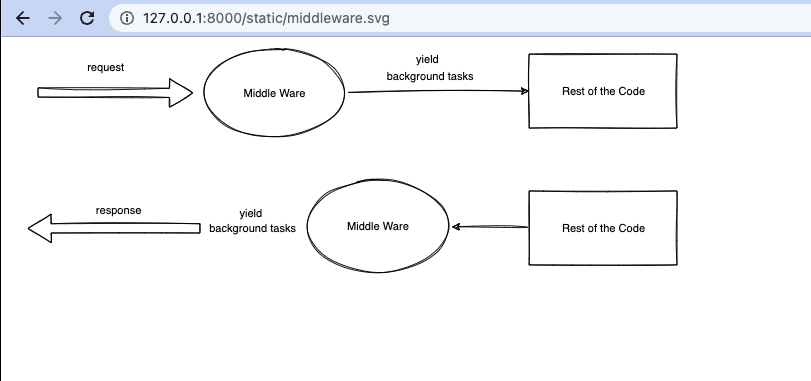

Middleware

A “middleware” is a function that works with every request before it is processed by any specific path operation. And also with every response before returning it.

from fastapi import FastAPI, Request

import time

@app.middleware("http")

async def add_process_time_header(request: Request, call_next):

start_time = time.time()

response = await call_next(request)

process_time = time.time() - start_time

response.headers["X-Process-Time"] = str(process_time)

return response

CORS (Cross-Origin Resource Sharing)

from fastapi.middleware.cors import CORSMiddleware

origins = [

"http://localhost.tiangolo.com",

"https://localhost.tiangolo.com",

"http://localhost",

"http://localhost:8080",

]

app.add_middleware(

CORSMiddleware,

allow_origins=origins,

allow_credentials=True,

allow_methods=["*"],

allow_headers=["*"],

)

@app.get("/new")

async def main1():

return {"message": "Hello World"}

SQL (Relational) Databases

You should have a directory named my_super_project that contains a sub-directory called sql_app.

sql_app should have the following files:

sql_app/__init__.py: is an empty file.sql_app/database.py:

from sqlalchemy import create_engine

from sqlalchemy.ext.declarative import declarative_base

from sqlalchemy.orm import sessionmaker

SQLALCHEMY_DATABASE_URL = "sqlite:///./sql_app.db"

# SQLALCHEMY_DATABASE_URL = "postgresql://user:password@postgresserver/db"

engine = create_engine(

SQLALCHEMY_DATABASE_URL, connect_args={"check_same_thread": False}

)

SessionLocal = sessionmaker(autocommit=False, autoflush=False, bind=engine)

Base = declarative_base()

sql_app/models.py:

from sqlalchemy import Boolean, Column, ForeignKey, Integer, String

from sqlalchemy.orm import relationship

from .database import Base

class User(Base):

__tablename__ = "users"

id = Column(Integer, primary_key=True, index=True)

email = Column(String, unique=True, index=True)

hashed_password = Column(String)

is_active = Column(Boolean, default=True)

items = relationship("Item", back_populates="owner")

class Item(Base):

__tablename__ = "items"

id = Column(Integer, primary_key=True, index=True)

title = Column(String, index=True)

description = Column(String, index=True)

owner_id = Column(Integer, ForeignKey("users.id"))

owner = relationship("User", back_populates="items")

sql_app/schemas.py:

from pydantic import BaseModel

class ItemBase(BaseModel):

title: str

description: str | None = None

class ItemCreate(ItemBase):

pass

class Item(ItemBase):

id: int

owner_id: int

class Config:

orm_mode = True

class UserBase(BaseModel):

email: str

class UserCreate(UserBase):

password: str

class User(UserBase):

id: int

is_active: bool

items: list[Item] = []

class Config:

orm_mode = True

sql_app/crud.py:

from sqlalchemy.orm import Session

from . import models, schemas

def get_user(db: Session, user_id: int):

return db.query(models.User).filter(models.User.id == user_id).first()

def get_user_by_email(db: Session, email: str):

return db.query(models.User).filter(models.User.email == email).first()

def get_users(db: Session, skip: int = 0, limit: int = 100):

return db.query(models.User).offset(skip).limit(limit).all()

def create_user(db: Session, user: schemas.UserCreate):

fake_hashed_password = user.password + "notreallyhashed"

db_user = models.User(email=user.email, hashed_password=fake_hashed_password)

db.add(db_user)

db.commit()

db.refresh(db_user)

return db_user

def get_items(db: Session, skip: int = 0, limit: int = 100):

return db.query(models.Item).offset(skip).limit(limit).all()

def create_user_item(db: Session, item: schemas.ItemCreate, user_id: int):

db_item = models.Item(**item.dict(), owner_id=user_id)

db.add(db_item)

db.commit()

db.refresh(db_item)

return db_item

sql_app/main.py:

from fastapi import Depends, FastAPI, HTTPException

from sqlalchemy.orm import Session

from . import crud, models, schemas

from .database import SessionLocal, engine

models.Base.metadata.create_all(bind=engine)

app = FastAPI()

# Dependency

def get_db():

db = SessionLocal()

try:

yield db

finally:

db.close()

@app.post("/users/", response_model=schemas.User)

def create_user(user: schemas.UserCreate, db: Session = Depends(get_db)):

db_user = crud.get_user_by_email(db, email=user.email)

if db_user:

raise HTTPException(status_code=400, detail="Email already registered")

return crud.create_user(db=db, user=user)

@app.get("/users/", response_model=list[schemas.User])

def read_users(skip: int = 0, limit: int = 100, db: Session = Depends(get_db)):

users = crud.get_users(db, skip=skip, limit=limit)

return users

@app.get("/users/{user_id}", response_model=schemas.User)

def read_user(user_id: int, db: Session = Depends(get_db)):

db_user = crud.get_user(db, user_id=user_id)

if db_user is None:

raise HTTPException(status_code=404, detail="User not found")

return db_user

@app.post("/users/{user_id}/items/", response_model=schemas.Item)

def create_item_for_user(

user_id: int, item: schemas.ItemCreate, db: Session = Depends(get_db)

):

return crud.create_user_item(db=db, item=item, user_id=user_id)

@app.get("/items/", response_model=list[schemas.Item])

def read_items(skip: int = 0, limit: int = 100, db: Session = Depends(get_db)):

items = crud.get_items(db, skip=skip, limit=limit)

return items

Alternative DB session with middleware

@app.middleware("http")

async def db_session_middleware(request: Request, call_next):

# It's probably better to use dependencies with yield when they are enough for the use case.

response = Response("Internal server error", status_code=500)

try:

# request.state is a property of each Request object. It is there to

# store arbitrary objects attached to the request itself, like the database session in this case. # For us in this case, it helps us ensure a single database session is used through all the request, # and then closed afterwards (in the middleware). request.state.db = SessionLocal()

response = await call_next(request)

finally:

request.state.db.close()

return response

def get_db(request: Request):

return request.state.db

It’s probably better to use dependencies with

yieldwhen they are enough for the use case.

Bigger Applications - Multiple Files

.

├── app # "app" is a Python package

│ ├── __init__.py # this file makes "app" a "Python package"

│ ├── main.py # "main" module, e.g. import app.main

│ ├── dependencies.py # "dependencies" module, e.g. import app.dependencies

│ └── routers # "routers" is a "Python subpackage"

│ │ ├── __init__.py # makes "routers" a "Python subpackage"

│ │ ├── items.py # "items" submodule, e.g. import app.routers.items

│ │ └── users.py # "users" submodule, e.g. import app.routers.users

│ └── internal # "internal" is a "Python subpackage"

│ ├── __init__.py # makes "internal" a "Python subpackage"

│ └── admin.py # "admin" submodule, e.g. import app.internal.admin

# app/routers / users.py

# Created by azat at 8.12.2022

from fastapi import APIRouter

router = APIRouter()

@router.get("/users/", tags=["users"])

async def read_users():

return [{"username": "Rick"}, {"username": "Morty"}]

@router.get("/users/me", tags=["users"])

async def read_user_me():

return {"username": "fakecurrentuser"}

@router.get("/users/{username}", tags=["users"])

async def read_user(username: str):

return {"username": username}

# app / dependencies.py

# Created by azat at 8.12.2022

from fastapi import Header, HTTPException

async def get_token_header(x_token: str = Header()):

if x_token != "fake-super-secret-token":

raise HTTPException(status_code=400, detail="X-Token header invalid")

async def get_query_token(token: str):

if token != "jessica":

raise HTTPException(status_code=400, detail="No Jessica token provided")

# app/routers / items.py

# Created by azat at 8.12.2022

from fastapi import APIRouter, Depends, HTTPException

from ..dependencies import get_token_header

router = APIRouter(

prefix="/items",

tags=["items"],

dependencies=[Depends(get_token_header)],

responses={404: {"description": "Not found"}},

)

fake_items_db = {"plumbus": {"name": "Plumbus"}, "gun": {"name": "Portal Gun"}}

@router.get("/")

async def read_items():

return fake_items_db

@router.get("/{item_id}")

async def read_item(item_id: str):

if item_id not in fake_items_db:

raise HTTPException(status_code=404, detail="Item not found")

return {"name": fake_items_db[item_id]["name"], "item_id": item_id}

# This last path operation will have the combination of tags: ["items", "custom"].

# # And it will also have both responses in the documentation, one for 404 and one for 403.

@router.put(

"/{item_id}",

tags=["custom"],

responses={403: {"description": "Operation forbidden"}},

)

async def update_item(item_id: str):

if item_id != "plumbus":

raise HTTPException(

status_code=403, detail="You can only update the item: plumbus"

)

return {"item_id": item_id, "name": "The great Plumbus"}

# app/internal / admin.py

# Created by azat at 8.12.2022

from fastapi import APIRouter

router = APIRouter()

@router.post("/")

async def update_admin():

return {"message": "Admin getting schwifty"}

# app / main.py

# Created by azat at 8.12.2022

from app.routers import items

from fastapi import Depends, FastAPI

from .dependencies import get_query_token, get_token_header

from .internal import admin

from .routers import items, users

app = FastAPI(dependencies=[Depends(get_query_token)])

app.include_router(users.router)

app.include_router(items.router)

app.include_router(

admin.router,

prefix="/admin",

tags=["admin"],

dependencies=[Depends(get_token_header)],

responses={418: {"description": "I'm a teapot"}},

)

@app.get("/")

async def root():

return {"message": "Hello Bigger Applications!"}

uvicorn app.main:app --reload

Background Tasks

# app_bgtasks / main.py

# Created by azat at 8.12.2022

from fastapi import BackgroundTasks, Depends, FastAPI

app = FastAPI()

def write_notification(email: str, message=""):

# And as the write operation doesn't use async and await, we define the function with normal def:

with open("log.txt", mode="w") as email_file:

content = f"notification for {email}: {message}"

email_file.write(content)

@app.post("/send-notification/{email}")